At a time when America’s political class has decided some people are too old to be president, the economy is pointing in another direction: The fastest-growing segment of the labor force is the 75-and-older worker.

While much of that growth is simple demographics – many baby boomers are moving into their 70s – it doesn’t appear to explain the entire phenomenon. For many Americans, working well into one’s 70s, 80s, or even 90s now seems preferable to full retirement.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Narratives of “too old” have become ubiquitous among pollsters, politicians, and pundits. But on Main Street, the hottest growth in the labor force is among workers well past traditional retirement age.

This surge in older workers is a boon to the United States as well as developed nations around the world. Still, the negative stereotyping based on age – known as ageism – persists.

That has not slowed down Pat Callahan, who, like many Americans, retired and then went back to work.

“This is my exercise,” says Ms. Callahan, who retired in her late 60s and a little over three years ago began working for her daughter’s startup, JM Move Managers, based in New Jersey.

Now in her mid-70s, Ms. Callahan spends 8 to 12 hours a week helping people discard or donate belongings. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked a job where people are so grateful for your help.”

At a time when America’s political class has decided some people are too old to be president, the economy is pointing in another direction: The fastest-growing segment of the labor force is the 75-and-older worker.

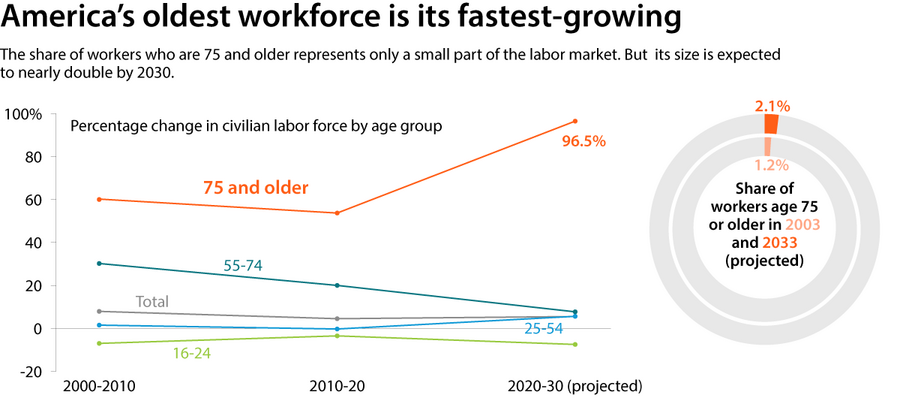

By 2030, the federal government projects, their numbers will nearly double.

While much of that growth is simple demographics – a huge contingent of baby boomers is moving into their 70s – it doesn’t appear to explain the entire phenomenon. For a growing share of Americans, working well into one’s 70s, 80s, or even 90s seems preferable to a full retirement.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Narratives of “too old” have become ubiquitous among pollsters, politicians, and pundits. But on Main Street, the hottest growth in the labor force is among workers well past traditional retirement age.

Some of them are famous, such as septuagenarian singer Dolly Parton and actor Meryl Streep, octogenarian actor Harrison Ford and musician Mick Jagger, and nonagenarian primate expert Jane Goodall and uber investor Warren Buffett.

“This is my exercise.” How older workers benefit the economy.

Then there’s Pat Callahan, who like many not-so-famous Americans retired and then went back to work.

Pat Callahan, who is in her mid-70s, recently went back to work with JM Move Managers in New Jersey.

“I’m not at the Y working out; this is my exercise,” says Ms. Callahan, who retired in her late 60s and a little over three years ago began working part time for her daughter’s startup, JM Move Managers. The Mountainside, New Jersey, company specializes in helping older people every step of the way as they downsize and move into new accommodations.

Now in her mid-70s, Ms. Callahan spends anywhere from 8 to 12 hours a week helping people discard or donate belongings, packing up what they want to keep and unpacking and organizing it in their new place. She even hefts boxes if they’re not too heavy, she says. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked a job where people are so grateful for your help.”

This surge in older workers is not unique to the United States. It provides benefits to developed nations around the world. It boosts the share of people contributing to the economy, provides needed workers at a time when some portions of the workforce are shrinking and, potentially, eases the pressure on retirement-benefits systems if it persuades governments to raise retirement ages.

Despite these benefits and the increasing visibility of people of traditional retirement age on the job, the negative stereotyping based on age – known as ageism – persists.

Learning to lift age-based labels

“Ageism is alive and well,” says Jacquelyn James, founder of the Sloan Research Network on Aging & Work at Boston College. “Anyone can make a joke about an older person. They’re a geezer, or they’ve ‘lost it.’ They can’t do the job or are slow. … The discussion about [President Joe] Biden has probably set us back quite a bit.”

SOURCE:

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

|

Jacob Turcotte/Staff

The problem, gerontologists say, is that rather than understanding physical and mental limitations as a specific challenge for a specific individual, such challenges are generalized as “getting old” and pinned to an entire segment of the population. The reality is quite different.

“I know a lot of guys who are in their early 80s who are still flying,” says Dana Lyon, a former Southwest Airlines pilot who at 65 took mandatory retirement and, 13 months later, started working again. In his late 60s, he now flies charter planes for a startup in Texas and plans to continue four or five more years, he says. “I love flying.”

While many of those working into their 70s have cut back their hours and consider themselves retired, some remain quite active. Bob Iger retired as Disney’s CEO at 70, spent less than a year in retirement and then returned to his post two years ago at the behest of the board of directors. At 84, Nancy Pelosi, while no longer speaker of the House, is active politically, and helped persuade President Biden, who is 2 ½ years younger, to end his reelection campaign last month.

Eli Trujillo poses inside his barbershop in Cheyenne, Wyomng. Mr. Trujillo, who is in his mid-80s, remains active, saying he doesn’t work as many hours or cut hair as fast as he once did.

More often than not, older people stay in their jobs rather than find new ones. This is especially true of professionals, such as lawyers and professors, as well as small-business owners, says Gary Burtless, a senior fellow emeritus at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

Second and third careers

Job-seekers over age 65 have a hard time getting employers to respond to their applications, let alone offer them a job, says Ms. James at Boston College.

But there are exceptions.

At Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute, older workers looking for a change take a year to explore possibilities. A neuroscientist is now publishing her wildlife photography; a professor is writing mystery novels, according to Katie Connor, the institute’s executive director. After working as an environmental engineer, founding a coffee company in Hong Kong, taking time off to raise her children, lecturing at the University of Colorado at Boulder and eventually running its career office, Ms. Connor came to the institute to figure out her next step. It turned out to be heading up the institute.

Thinking outside the box is a big factor in a successful transition, she says, as well as “being curious and being willing to be a beginner. It can make all the difference. … There are structural problems [for older job-seekers looking for a change]. But I also think there are problems in our own mindset about aging.”

Want to work versus need to work

The rise of older workers also has its darker side.

Roughly half of those on the job working past age 65 are working because they have to, not because they want to, says Craig Copeland, director of wealth benefits research at the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a policy research nonprofit in Washington. About 1 in 3 older adults is economically insecure, many of them Black or Hispanic, according to the Census Bureau.

Another downside is that boomers hanging onto higher, better-paying jobs can breed resentment among younger workers. “The young guys, they go: ‘You’re taking my spot. You’re an old man. Get out of there so I can move up,’” says Mr. Lyon, the pilot.

The visibility of such workers can increase envy and even ageism, especially if the older workers are struggling at their jobs, Teresa Ghilarducci, an expert on retirement security at the New School for Social Research in New York, writes in an email. But “on balance, older workers overcome ageism. [Ms. Pelosi] has never been more effective. … She is old and probably still peaking.”