In April 2011, I headed to Milan for the first time to report on the annual Milan Design Week. There, I also visited the Triennale Design Museum, housed in the Palazzo dell’Arte. Designed by Italian architect Giovanni Muzio, it was completed in 1944, but AMDL Circle renovated the interiors in 2002.

The multidisciplinary design studio helmed by Michele De Lucchi suspended a bamboo footbridge across the main stairwell, connecting galleries, and altering perception and possibilities of the void. I did not realise it then but during those few hours, I would encounter many more of De Lucchi’s genius.

For example, at the Triennale’s bistro during lunch, I sat on anthropomorphic Bisonte stools that De Lucchi designed with Philippe Nigro. At the Triennale’s bookstore, wanting to buy a book I could easily bring back to Singapore, I reached for De Lucchi’s 12 Tales with Little Houses, featuring 12 wooden structures the architect-cum-artist made with a chainsaw (more on that later).

Wandering through the exhibit Dream Factories that celebrated modern Italian design icons, I spotted De Lucchi’s Tolomeo lamp, created together with Giancarlo Fassina in 1986. It is one of the world’s best-selling lamps today, with lighting manufacturer Artemide dedicating an entire factory to produce the Compasso d’Oro prize-winning luminaires.

All this backstory to come to the point 13 years later when I finally meet De Lucchi at the house of Dante Brandi, Italy’s ambassador to Singapore. They are good friends, and Brandi had invited De Lucchi to town for Singapore Design Week (held from Sep 26 to Oct 8, 2024) as the event coincided with Italian Design Day in Italy.

Tall and easily recognisable with his trademark beard and spectacles, De Lucchi is soft-spoken but not shy. He speaks freely and is amiable, a person you can immediately be friends with. He has no airs about him, despite having a prodigious portfolio and reputation.

Yes, in the creative circle, De Lucchi is a sort of legend. Aside from having designed furniture and objects for brands like Poltrona Frau, Cassina, Alessi, Hermes, Vitra and Olivetti where he was director of design between 1992 and 2002, he has conjured up impactful structures like the Bridge of Peace in Tbilisi, Georgia and amazing pavilions including those for the World Expo 2015 in Milan. For Expo 2025 Osaka, De Lucchi designed the cradle-to-cradle Nordic Pavilion that can be dismantled and reused elsewhere.

The day after dinner at Brandi’s house, I sat down with De Lucchi for an interview. What does he like about Singapore, I asked. “Gardens by the Bay, because it’s quite an unusual attraction made with just nature. And it’s beautiful,” he replied.

The city’s greenery and modernity is a contrast to Milan, where AMDL Circle is based. Milan is a city of old structures, said De Lucchi. “They’re just made of stone but are so meaningful, embodying the history of Milan and reflecting where we came from. These stone buildings, made 2,500 years ago, are so much more solid than the buildings we have today.”

Yet, while he appreciates these ancient constructions, De Lucchi is not nostalgic. He recognises that today’s architecture needs to be adaptable to dynamic advancements in technology, science and information. For example, new energy sources will alter the way mechanical and electrical services are housed in buildings, opening up new design opportunities.

De Lucchi has always been a renegade, optimist and advocate for progress. After all, AMDL Circle’s first project was “a crazy installation in the quarries where I was living to fight against big companies that were demolishing mountains.” His beard is also an act of rebellion. “I have a twin brother. That’s the reason why I wanted a beard,” he chuckled.

Born in Ferrara, Italy in 1951, De Lucchi was brought up in Padua. He and his twin brother were consistently referred to as a single entity by his parents, resulting in an innate quest for a singular voice. The artistic youth veered from the expected course of being a structural engineer (as were his father and some of his brothers). “I wanted to go to art school, but my father wanted me to study engineering. So I compromised with architecture,” De Lucchi shared.

It was then that he separated from his twin brother, who stayed in Padua to study chemistry. De Lucchi ventured farther to study architecture at the University of Florence. The profession he initially perceived as a trade-off eventually turned out to be “the best possible decision”.“I got a bit more independence there. When it was possible, I started my own practice. Little by little, I became aged,” mused the 72-year-old. I commented that he is still humourous. De Lucchi laughed, and said: “That’s a compliment. I want to be funny. In a sense, if we face architecture in a more relaxed way, it’s much better.”

It is true that De Lucchi’s works try not to take themselves too seriously. Even in tackling serious issues, there is subtlety, wit and poetry. For example, while his glass, timber and bronze mobile post office in the archaic St Peter’s Square is unapologetically contemporary, its polygonal plan pays respects to Italian architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s rounded layout. On a smaller scale, De Lucchi’s Pulcina coffee maker for Illy was inspired by a chicken, with a beak-like spout that prevents drips after pouring.

As a student and young architect during the tumultuous 1970s and 1980s De Lucchi was involved in movements like Architettura Radicale and Alchimia. “That was a wonderful time,” he recalled on meeting exciting, like-minded architects. One was Adolfo Natalini, the founder of Superstudio, for whom De Lucchi was an assistant. Rejecting design as a tool for consumerism, the progressive architecture group pushed for more meaningful and egalitarian thinking in design.

And of course, we cannot speak with De Lucchi without discussing one of his greatest rebellions via the Memphis Movement. From 1981 to 1987, the founding member of the group, together with his mentor Ettore Sottsass and other renowned architects, challenged Modernism’s status quo with colourful and bizarre furniture and household objects, which incorporated commonplace materials like laminate and terrazzo, as well as decorative motifs referencing exotic cultures, art deco and pop art.

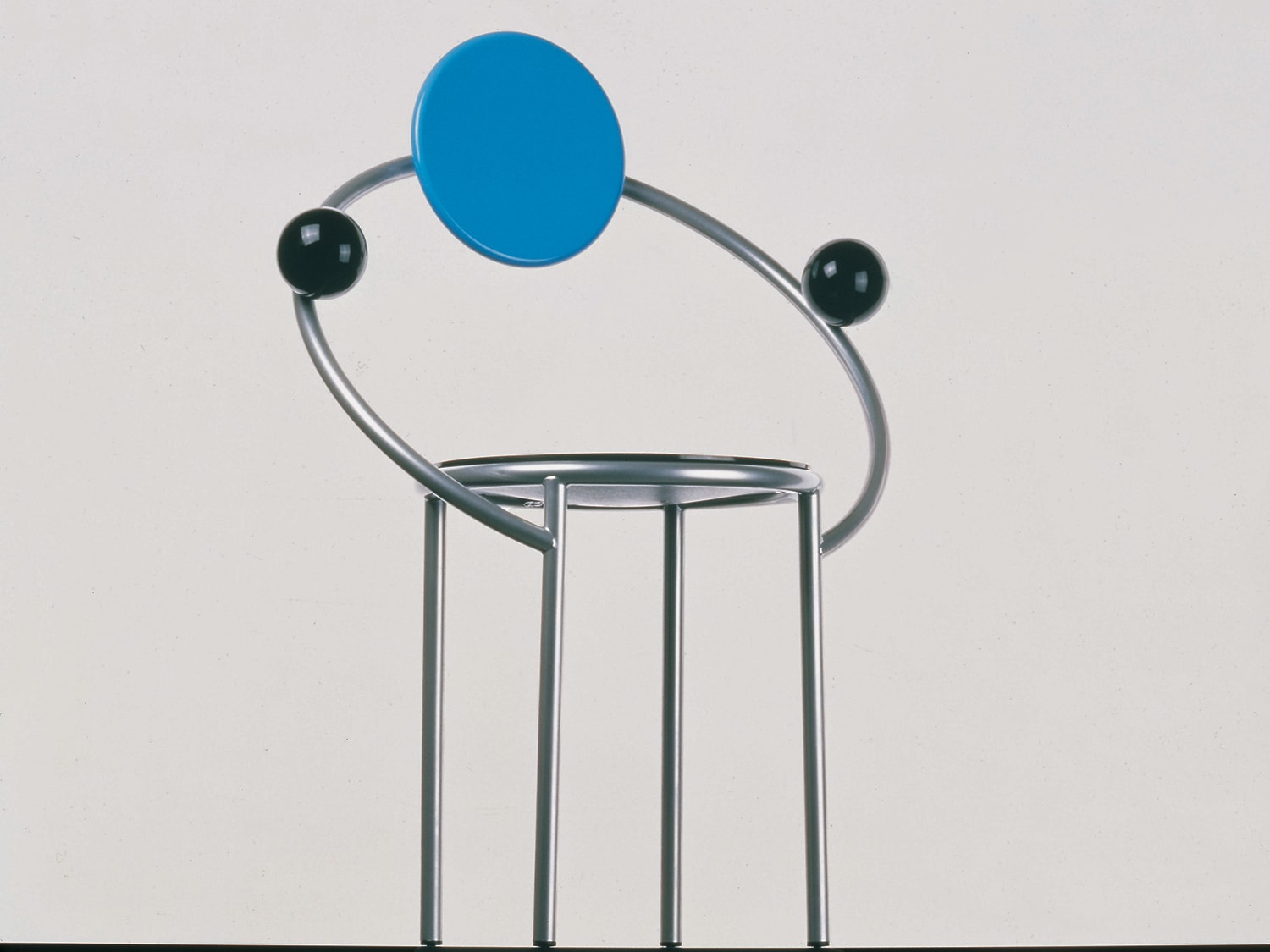

Their far-reaching ethos heavily impacted the ‘retro’ and street aesthetic of the mid-1980s to early 1990s; fashion mavericks like Karl Lagerfeld and David Bowie were fans and collectors, with the latter’s Memphis pieces famously auctioned off at a recent Sotherby’s auction. De Lucchi’s designs for Memphis include the geometric First Chair and the Lamp Oceanic – his stripped, comical version of a sea creature.

“Memphis was very extraordinary because it was a movement that connected people all around the world. People understood the change that was happening at that time in the same moment. There was the same perception of creating something new,” said De Lucchi. I commented that Memphis has made a come back of late. De Lucchi responded: “Yes, it’s very iconic, very fashionable today. Memphis was to fight against convention. That was the message of Memphis then, and that is the message of Memphis today.”

Much of the discussion at Memphis was on the architect’s role. “How should we contribute to life? Is it only building skyscrapers? Was it simply a technical profession? We thought, no. Because when architects design buildings, they are also designing for the people inside the rooms. We thought that the role of the architect should be closer to society, to investigate how to create a more gratifying life for people.”

Whenever he lectures around the world, De Lucchi reminds architects that they are paramount in bringing positivity to the world. “A pessimistic architect is a disaster; we don’t need pessimistic architects,” he stressed. On the other hand, architects should be given more credit for their contributions to society and to the world.

In his own work, De Lucchi has benefited from breaking out of the box. “I am not only an architect, but also a designer; I work for companies, but I also work for myself as an artist and sculptor,” he commented. Each role feeds the other. De Lucchi explained: “Art is very important because the artist has new ways of interpreting reality and do so without the responsibility of understanding if it’s right or wrong. A designer has the responsibility to pick up everything else and translate them into industrial production and buildings.”

On that aforementioned chainsaw, De Lucchi has been carving timber sculptures with this tool since 2004. “All my buildings, they come from my sculptures, because they are the most efficient way to experiment on shapes and forms,” said De Lucchi, who favours wood not just for sculpting but also for his built works.

In the book 12 Tales with Little Houses, De Lucchi wrote about this material: “I love it’s meekness, the way it first lets itself be worked and then rebels and reacts irreverently to change as it dries and ages. Nothing can tame it; it moves, twists, develops veins and cracks, unconstrained by either rules or limits, at times managing to ruin days and days of hard work. But wood is wonderful for the way it stays so full of life even after years and years.”

De Lucchi could very well be speaking about himself. These sentiments are echoed in a recent upload to writing platform Substack (De Lucchi is a regular – and earnest – writer) where he sums up his creative life: “As a young man, I suffered greatly from an inability to choose a clear and single discipline to which to devote my energies and direct my efforts. I told myself I wanted to be an architect but then I found myself among radical architects and challenged the traditional idea of the architect by saying that architects do not make houses but inspire behaviour.

“I became a designer and complained that I didn’t like the perfection and monotony of machine-made things. I started to be a painter but I wasn’t satisfied with the shapes I drew, and I started to carve them in wood and became a sculptor. Now even that is not enough for me anymore and I want to tell the ideas myself and so I tell stories nonstop. And after 50-plus years of changing course, I realise with surprise how fortunate this indecision was and how much I have enjoyed approaching the world of spaces and objects from so many different angles.”